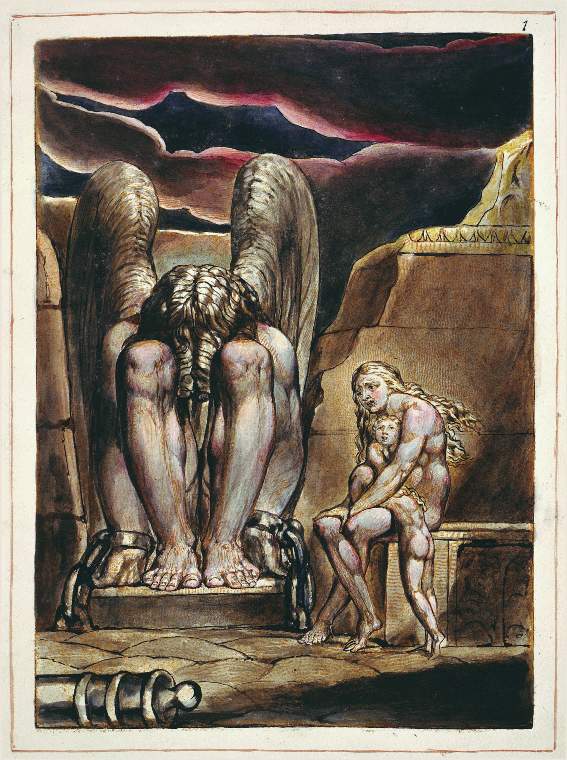

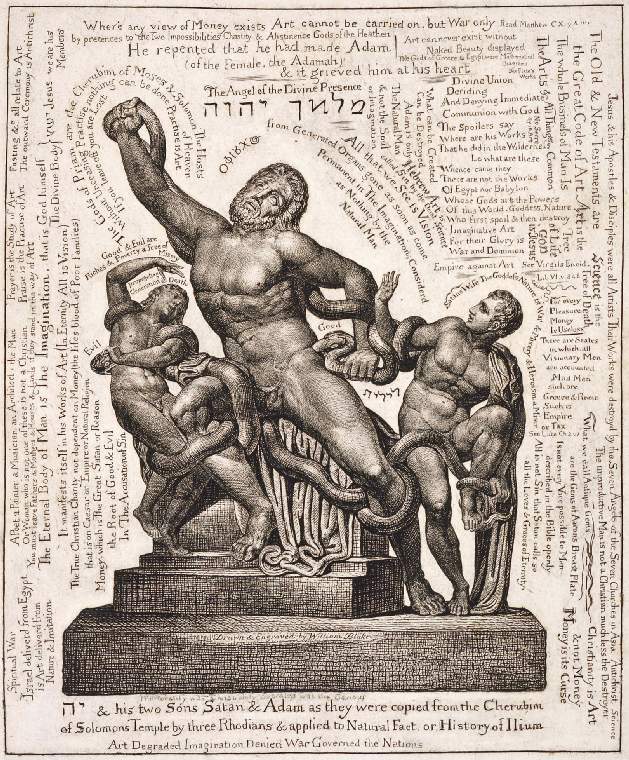

It's never a good thing if the main memory of an exhibition is the colour of the walls. Sadly, the Fitzwilliam's William Blake's Universe will forever be linked in my mind with the daffodil yellow of the final room. Strong colours are the fashion of the moment (a moment which is hopefully reaching its end) but they are always intrusive, an assertion of curatorial presence, even when you agree with the choice, and that intrusiveness is magnified in an exhibition of mainly small-scale prints and drawings where there is so much more wall on show.

Wednesday, April 24, 2024

'William Blake's Universe' (Fitzwilliam Museum until May 19 2024): Trying Too Hard to be Universal

It's never a good thing if the main memory of an exhibition is the colour of the walls. Sadly, the Fitzwilliam's William Blake's Universe will forever be linked in my mind with the daffodil yellow of the final room. Strong colours are the fashion of the moment (a moment which is hopefully reaching its end) but they are always intrusive, an assertion of curatorial presence, even when you agree with the choice, and that intrusiveness is magnified in an exhibition of mainly small-scale prints and drawings where there is so much more wall on show.

Monday, April 15, 2024

Angelica Kauffman (Royal Academy until June 30 2024): More Than Just a Woman Artist

Tuesday, April 9, 2024

'Frank Auerbach: The Charcoal Heads' (The Courtauld until May 27 2024): Creative Destruction

Auerbach is no ordinary portraitist. His subjects are familiar, familial, himself, seen here in repeat. He observed them over months, each sitting recorded and erased in a process of layering and repeat. The time and process are writ large in scuffs and tears and mends: whilst Auerbach's oils seem often a process of building up, here he is constantly breaking down. It is one of the many contradictions. Works which have been produced so slowly are utterly immediate, a flash of dynamic lines. Faces in close-up scale largely avoid our gaze, with hollows for eyes which tilt down or turn aside. Line and structure are etched with a rubber. Never has creation seemed so destructive.

There is no context given to these figures - no background, no space, little detail - but once you know the context, rawness hangs acrid in the air. Auerbach's own tragedy, refugee child of parents murdered in Auschwitz, and the long, lingering shadow of the Second World War: physical and mental scars, visible wounds, patches of poverty and endless, endless grey. The occasional slash of colour seems like an attack rather than a respite. The faces take on a ghoulish emptiness, stripped back, almost genderless. Yet the final, greatest paradox of this show is that humanity triumphs in the end. Auerbach's self portraits are thoughtfully challenging in their strong, straight stare. His cousin, Gerda Boehm, another refugee, his substitute parent, retains her poise and gentility. Helen Gillespie is all angles and sharp edges, positively glinting with wit. These characters breath and move, with subtle shifts of pose, lighting and expression across the different charcoals. Not ghosts after all.

Wednesday, April 3, 2024

'Entangled Pasts: 1768–now Art, Colonialism and Change' (Royal Academy until 28 April 2024): Difficult to Disentangle

In their absence, however, is blandness and vagueness. Too often I was left wondering why? Why was John Singleton Copley there? Because he, like Benjamin West was American, although there was no attempt to analyse their unique position as colonial but white? Because of the Black figure ignored in a caption which focuses instead Watson's survival to become Mayor of London? Because Copley was a big eighteenth century name they could get hold of? Similarly, Bowling and Gallagher are part of a room dedicated to the sea which is split awkwardly between the Middle Passage and whaling with a couple of second-rate Turners for good measure. The 'Constructing Whiteness' display feels especially thrown together. Frank Dicksee's laughably awful Startled doesn't need a caption which ties itself in knots over 'aryanising', 'nordic' and 'classical'. The slippery language emphasises a nettle ungrasped: issues of Academy racism are taken up to the Second World War and then glossed over. Surely this was the moment to acknowledge the embarrassing truth that Sonia Boyce, the first Black female academician, was only elected in 2016.

'Entangled Pasts' raises obvious comparisons with the recent, albeit much smaller, 'Black Atlantic' exhibition at the Fitzwilliam Museum - even some of the same works are on show. The Fitzwilliam went for tightly written text and impeccable lighting to create nuance and structure and maximise their limited exhibits. The Royal Academy, in contrast, underuses Barbara Walker's Vanishing Point and the beautiful Man in a Red Suit is shown, along with fine portraits by Gainsborough, Reynolds and others in a gloomily empty octagon. Isaac Julien's film deserves a better space: crowded watchers jostle with those trying to get through to the sculptures beyond and the tintypes behind are impossible to see. Meanwhile, Lubaina Himid's Naming the Money installation sprawls over two rooms, its impact lessened as a result. Inevitably, with 100 works and 50 artists, there are weaker pieces and you could certainly make the case for some judicious pruning.

In some ways 'Entangled Pasts' is a show of (mainly) good art, poorly served. But maybe that doesn't matter. Its big, rambling, inconclusiveness is in itself a metaphor for the entangled past it's seeking to represent. There are no easy answers or straightforward narratives. There are questions and problems and dead-ends. The curators resolutely refuse to tell us what to think, but thank goodness for that. What the show does - and arguably what it could have done even more - is pit the past against the present and let the results speak for themselves. Let's have more of the same.

Sunday, February 25, 2024

'Sargent and Fashion' (Tate Britain until Jul 7 2024): Fashion might be in Fashion, but Sargent is the Star

Sargent and Fashion is an awful title. I went to the exhibition with a feeling of dread: women sitters as clothes-horses and John Singer Sargent reduced, as he so often is, to celebrity portraitist. And yes, there are dresses and fans and feathers, but they enhance, not detract from, the paintings. The real reason to go, is to see a wonderful collection of Sargent's portraits, many of them from the United States, some of them never seen before in the UK. Fashion is something of a fashion at the moment: the Ashmolean recently linked art, objects and clothes in its Colour Revolution show and Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery is currently exhibiting dresses alongside its Pre-Raphaelites. Personally, I can take it or leave it: dresses are no different from other 'ephemera' which gets included in exhibitions as context. Like photographs or letters, or the rococo furnishings which Dulwich included in the exhibition last year to elucidate their claims about Berthe Morisot's 18th century influences, clothes can be helpful. But for me it remains all about the art.

Sargent is too often and too easily dismissed as a portraitist and whilst this exhibition sticks firmly to his representations of people, it is obvious, even from the first couple of rooms, that he isn't 'just' a painter of portraits. Equally, he is an artist who overlaps with Impressionism, both chronologically and personally - there is a lovely anecdote about his dismay in visiting Monet and finding no black paint in the house - yet is most emphatically not an Impressionist. In the context of innovation-obsessed art history, this makes him seem like a fuddy-duddy throwback, churning out Grand Manner portraits whilst the modern world moves on around him. Yet there is nothing staid about Sargent, or, one suspects, despite their corsets, about his sitters.

Sargent's female subjects are anything but clothes-horses. Many were personal friends, many he painted more than once, and the closeness shows. He is a master at finding the telling detail, the revealing tic. Madame X, so often seen as a cypher for unobtainable sexual allure because of that infamous drooping strap, in reality betrays a brittleness. You see it in that sharply profiled, retrousse nose and the thumb tensed on the polished wood table. Vernon Lee sparkles with vitality, like electricity crackling: the reflection on her glasses, the sheen on the end of her nose, the moist, mid-conversation lips and the random dashes of white above her eyebrows, under her chin. You are desperate to hear what she has to say. Mrs Edward L Davis strides out of the canvas with her mouth set and her hand on her hip, her skirts smothering her sailor-suited son whose hand she holds iron-fast. You fear for his future wife - she's never going to let him go.

The clothes are just as important. Not fashion, not decoration, but integral to the character of their wearers. They give Mrs Edward Darley Boit her engaging energy - all polka-dots and swirls with a flame-like feather rising from her head. She's straight out of Henry James, the life and soul of every dinner party and, boy, does she go to a lot. They define the differences between sisters Betty and Ena Wertheimer: the quiet, pretty one, and the character who'll go on to play act for Sargent in borrowed robes. And of course, Sargent the artist uses clothes for his own purpose, pleasure and challenge. Black on black, white against white, dramatic colour contrasts, texture and pattern. Is fashion the right word for all this creativity with cloth?

If the curators get the title wrong, then they also over-egg their labelling with dressy details. I don't feel the need to have a written description, even if it is from a contemporary source, of an outfit which is literally next to it, either on canvas or in a vitrine. They have also succumbed to the fashion for eccentric wall colouring: here including a particularly nasty orange. A major gripe is the room which looks at Sargent's performativity and fluid representation of gender. Again, these are buzz themes which are easily overcooked and what the three 'masculinities' on display really show is the painter's ability to render character. Waif-like in his attenuated pallour, Graham Robertson is a 19th century Timothée Chalamet, so elegantly fragile he seems held vertical only by the tight rigidity of his coat. In Dr Pozzi at Home, the surgeon's fingers pluck delicately at the fabric of his floor-length red dressing gown, giving him an edgy femininity which the clothes alone do not. Between them, Henry Lee Higginson lounges in self-confident tweed, chin up, holding our gaze with a sense of impatience. Performance seems a superficial dismissal of these careful, subtle character studies.

What the curators get wonderfully right, however, is the expansive range of Sargent's work. They cover his idiosyncratic portraits of children, and of Robert Louis Stevenson and his wife; his theatricality including the masterly Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth; his dabbles in aestheticism, not just Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose but the ethereal Cashmere, paint as soft as the fabric itself. The small, late landscapes where strangely posed figures are swallowed up by verdant vegetation have a unique, abstracted mood. Fashion and character are not the issue here, you sense the impatience of an artist who just wants to experiment with paint, with form. Fabrics become watery pools, dappled with sunlight, clefted with shadow. Features blur into nothingness.

Sargent and Fashion might be an awful title, but it's clever marketing, and the exhibition is bound to be a success, attracting art lovers, clothes lovers and those for whom rooms full of elegance (male and female) have its own appeal. If the curatorial argument seems weak, then the paintings simply speak for themselves. Ultimately, Sargent is about so much more than fashion.

Saturday, January 27, 2024

'Dame Laura Knight - I Paint Today' (Worcester City art Gallery and Museum until June 30 2024): Just Scratching the Surface

It is impossible to do justice to a career as long and prolific as Laura Knight's in two very small rooms, and you can leave Worcester Art Gallery's I Paint Today feeling disappointed by the absences. There is very little of her early work: the soft shadows of a Staithes interior leaves you desperate for more, and two sun-baked clay pits noisy with labour are the only hint of her breezy, endless-summer Cornish coastal scenes. There is just one of her incredible series of works for the War Advisory Committee - but, boy, is it good. And a whole wall is given over to her husband's paintings, including two large, similar society portraits, in what seems a frustratingly unnecessary act of gender balance.

What you do leave with, however, is a sense of Laura Knight's range and variety. Partly this is a product of a long life, lived determinedly in the present (here the title of the show seems particularly apposite). Knight started as a late nineteenth century naturalist, befriended by George Clausen, influenced by Dutch and French art; she became increasingly Impressionistic, embracing a richer almost Bloomsbury-esque palette during the 1930s, before employing her portraitist's eye for the observed realism of her wartime paintings. But her output is not just an accident of longevity. Knight was constantly exploring and experimenting, from acquiring Clausen's printing equipment for her own etchings, to jewellery, ceramics, and London Transport posters. In a small space, the Worcester curators give a sense of all this and more.

In some ways it's a messy exhibition. The chronology dots about, the thematic approach seems governed by availability of works as much as by any coherent plan. There are, for me, too many of Knight's circus and Gypsy subjects, presented here without comment despite their potentially problematic representations. Whilst The Grand Parade, Charivari has an unintentional surrealism, her backstage theatricals seem polite and dated. However, the curators' efforts are also clear: there are loans aplenty, good, sensibly written wall texts and even some afternoon talks. Could it have been a better exhibition if it focussed on one aspect of her work - perhaps. The local interest connection of the Malverns, the subject of a 2020 book by Heather Whatley, could easily have become the theme of the show.

Laura Knight suffered under the modernist hegemony of the late twentieth century: she was too naturalistic, too figurative, and far too establishment. Thankfully, she is now gaining the attention she deserves and if the exhibition at Worcester introduces more people to her variety and her talent it will be a good thing. I Paint Today might not be the best exhibition you'll go to, it certainly isn't the best exhibition of Knight's work that I've seen. But it contains at least one masterpiece: Take-Off, Interior of a Bomber is big and bold and utterly compelling in its juxtaposition of calm observation and impending tragedy. A display of Knight's wartime paintings - now that would be a grand thing indeed.

Sunday, January 21, 2024

'Pesellino: A Renaissance Master Revealed' (National Gallery until March 10 2024): Delight in Detail

A single, dark room in the National Gallery shimmers with colour and pattern and detail. It feels intimate and otherworldly after the cavernous spaces and damask walls of the main displays; even busy with people there's a hushed, chapel-like atmosphere. Pesellino is not a 'big name' but you walk out thinking he ought to be. There is something so joyously exuberant about his art, so crazily outlandish. Why add pink marshmallow clouds to his King Melchior Sailing to the Holy Land ? Why surround his Pistoia Crucifixion with surreally-weird disembodied putti? Why have a bear cub snuffling in the foreground of David's grand victory parade? Just for the hell of it, for the brash Icarus-like, 'look at me fly' nerve of it. Even without knowing the tragedy of his early death from the plague, you have to love the guy.

Pesellino was at the centre of artistic life in Florence, at a time when Florence was pretty much at the centre of artistic life; he worked with big names like Filippo Lippi, he worked for big names like the Medici, who commissioned the David panels here. He was also a canny operator: illuminated manuscripts, devotional diptychs, furniture. You get the idea that if the price was right, and the patron was right, then Pesellino, like most of the artists of the day, would turn his hand anything. He lived right in the middle of that exciting, anything-is-possible time in the midst of the fifteenth century when new - Masaccio's perspectival experiments - and the old - pattern and gold and natural detail - coexisted in a gloriously chivalrous battle. You can see Uccello's San Romano in Pesellino's foreshortened knights and stylised horses; you can see Botticelli's elegant angels their draperies blowing in the breeze; you can see Gentile da Fabriano's gilded luxury. But if that all makes, Pesellino sound like an artistic magpie, nicking the others' best ideas, you'd be wrong. There is also something uniquely, idiosyncratically him.

The little exhibition also showcases the National Gallery. They do this kind of thing so impeccably well that you forget the time and effort (and money obviously) which goes into even a one-room exhibition like this. We owe them for originally gathering together the hacked up pieces of the Pistoia altarpiece, now united. We owe their conservation team their labour in restoring the battered furniture panels of the cassone, with their visible key marks. We owe the curators for having the foresight to see that this was a show worth having and reaching out to get loans like the King Melchior. And most of all, we owe them for not charging an entrance fee. It would be very easy for the gallery to rest on its laurels, put on the big shows and watch the visitors come through the doors, but, as anyone who visits regularly knows, they are constantly tweaking, moving, changing; and always producing these mini-displays. You can also see Jean-Étienne Liotard's pastels at the moment.

So, go! Make use of the magnifying glasses provided, the excellent key which clarifies the complex multiple scene-narrative of the David panels, and the conservation video which shows just how mind-blowingly skillful Pesellino was in his pre-application of tiny gold leaf details. But most of all just go and enjoy some of the best art you'll see this year. By a guy who never even makes it into the history books.

'Millet, Life on the Land' (National Gallery until October 19 2025)

Jean-François Millet, The Wood Sawyers, c.1851, Victoria and Albert Museum, London It has been a very long time since the last exhibition de...

_-_The_Wood_Sawyers_-_CAI.47_-_Victoria_and_Albert_Museum.jpg)

-

Johannes Vermeer Girl with a Flute 1669-75, National Gallery of Art Washington The National Gallery of Art in Washington recently reported...

-

Milking Time , undated, St Louis Art Museum Willem Maris (1844-1910) was a Dutch artist, one of three brothers who were all associated with ...

-

Donatello, Judith and Holofernes , c1455. Palazzo Vecchio Florence If you ignore the crowds around the replica of Michelangelo's David i...

_-_Self_Portrait_of_the_Artist_Hesitating_between_the_Arts_of_Music_and_Painting_-_960079_-_National_Trust.jpg/800px-Angelica_Kauffmann_(1741-1807)_-_Self_Portrait_of_the_Artist_Hesitating_between_the_Arts_of_Music_and_Painting_-_960079_-_National_Trust.jpg)