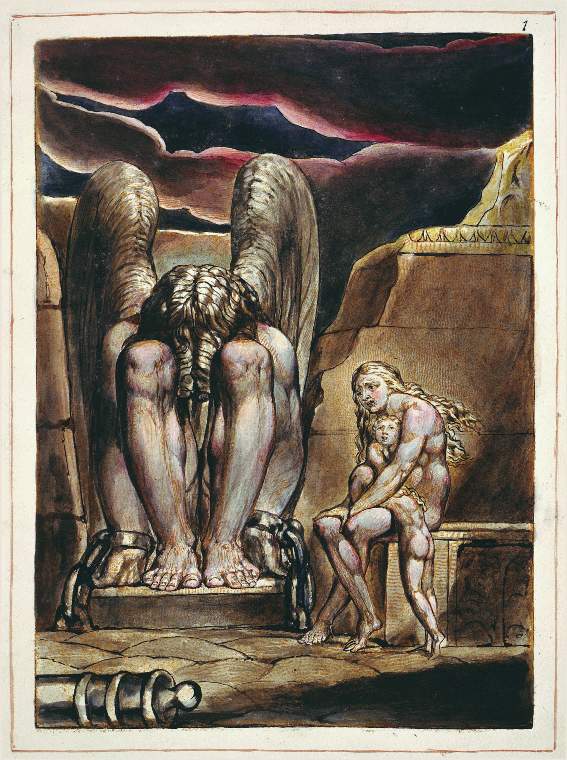

William Blake, America, A Prophecy, 1793, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

It's never a good thing if the main memory of an exhibition is the colour of the walls. Sadly, the Fitzwilliam's William Blake's Universe will forever be linked in my mind with the daffodil yellow of the final room. Strong colours are the fashion of the moment (a moment which is hopefully reaching its end) but they are always intrusive, an assertion of curatorial presence, even when you agree with the choice, and that intrusiveness is magnified in an exhibition of mainly small-scale prints and drawings where there is so much more wall on show.

I have doubts about other curatorial choices too. The Fitzwilliam Museum has a wonderful collection of Blake's work and you can imagine the conversation about how it might be exhibited afresh. The decision to link him to Otto Runge and Caspar David Friedrich is boldly idiosyncratic. These are artists who didn't meet or really know of each other's work, whose points of artistic confluence are few. There's an interesting intellectual case to be made, but there is not enough integration in the display of the works, and, in Friedrich's case, the examples are poor. I suspect, given the enthusiasm with which his 250th anniversary is being celebrated across Germany, this is not the best year to borrow Friedrichs. The vagueness of these European connections is particularly frustrating because the exhibition touches on stronger British links and influences - Fuseli, Barry, Linnell, Palmer. In the case of John Flaxman especially, there is the nugget of a fascinating show: better known for his sculpture, Flaxman has been relegated to the status of Neoclassical also-ran alongside Antonio Canova, yet his drawings here have a beautiful clarity and economy of line.

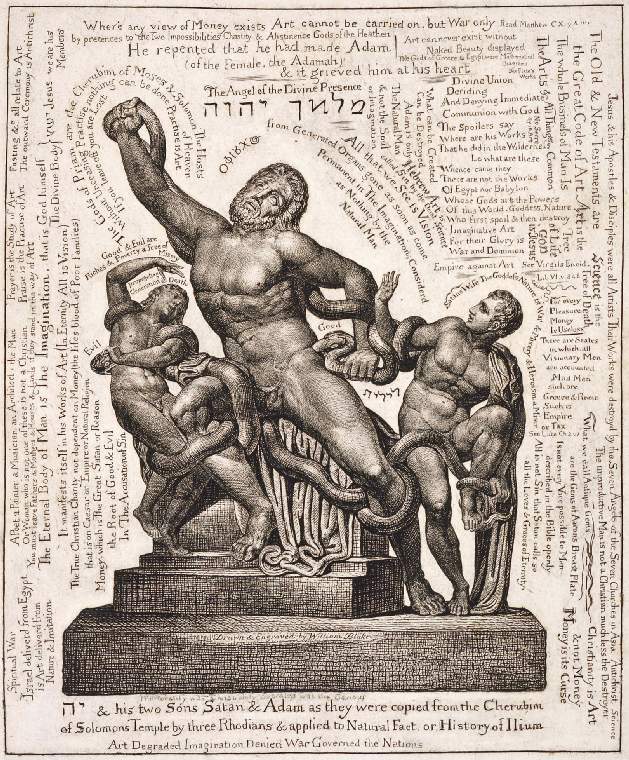

The exhibition also takes a lot of time to get going. A first portrait gallery (deep purple) creates a fine sense of the characters involved. Some are familiar - like the wary, slightly petulant intensity of Palmer's self image - some less so. Catherine Blake's posthumously remembered image of her youthful husband is loving and lively, a far remove from the portly middle age that we usually see. But the second room squanders those personalities in a meander through Academy practice and the, in Blake's view, malign influence of classicism. In reality, the artist's viciously annotated Laocoön is really all you need.

In the end, this exhibition is about William Blake and it really takes off in the flame-coloured third room where there are some wonderful examples of his work: rich colours, heavily anatomised figures, impossibly attenuated poses, flowing beards. The Songs of Innocence and Experience are ignored in favour of a brave attempt to explain and contextualise his religious and political works (sadly hampered, it has to be said, by poorly applied wall texts with missing letters and half-visible words). Blake's universe and the characters which inhabited it are extraordinarily complex and it is a credit to the curators that I left the exhibition feeling as if I understood at least part of what he was trying to say. What is even more clear is the repeated visual language, the idealised youths, repressive old age, colourful angels, figures flying skywards, spiralling curves and natural motifs. And the depth of that influence, not just in his immediate acolytes, like Palmer, who synthesised his style into a quaint and utterly unBlakean conservatism, but through the nineteenth century to Art Nouveau illustrators, into German Expressionism and beyond - surely Tolkien was familiar with his work.

William Blake is a difficult artist to exhibit. Many people find him a difficult artist to like. Some might argue he is better seen as a poet who illustrated his own work. But the Fitzwilliam exhibition - when it focuses on him - is utterly convincing and compelling. It ends with some of the smallest, most intense works, intricate monochromes from the Book of Job. The whole universe is condensed into these tiny squares: Blake's ideas, his aesthetics, his humanity. And it's enough.

No comments:

Post a Comment