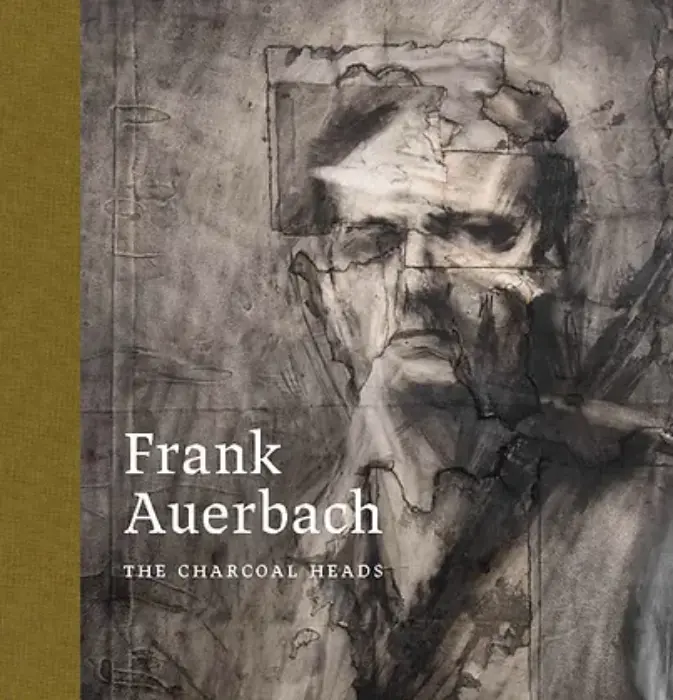

Auerbach is no ordinary portraitist. His subjects are familiar, familial, himself, seen here in repeat. He observed them over months, each sitting recorded and erased in a process of layering and repeat. The time and process are writ large in scuffs and tears and mends: whilst Auerbach's oils seem often a process of building up, here he is constantly breaking down. It is one of the many contradictions. Works which have been produced so slowly are utterly immediate, a flash of dynamic lines. Faces in close-up scale largely avoid our gaze, with hollows for eyes which tilt down or turn aside. Line and structure are etched with a rubber. Never has creation seemed so destructive.

There is no context given to these figures - no background, no space, little detail - but once you know the context, rawness hangs acrid in the air. Auerbach's own tragedy, refugee child of parents murdered in Auschwitz, and the long, lingering shadow of the Second World War: physical and mental scars, visible wounds, patches of poverty and endless, endless grey. The occasional slash of colour seems like an attack rather than a respite. The faces take on a ghoulish emptiness, stripped back, almost genderless. Yet the final, greatest paradox of this show is that humanity triumphs in the end. Auerbach's self portraits are thoughtfully challenging in their strong, straight stare. His cousin, Gerda Boehm, another refugee, his substitute parent, retains her poise and gentility. Helen Gillespie is all angles and sharp edges, positively glinting with wit. These characters breath and move, with subtle shifts of pose, lighting and expression across the different charcoals. Not ghosts after all.

No comments:

Post a Comment