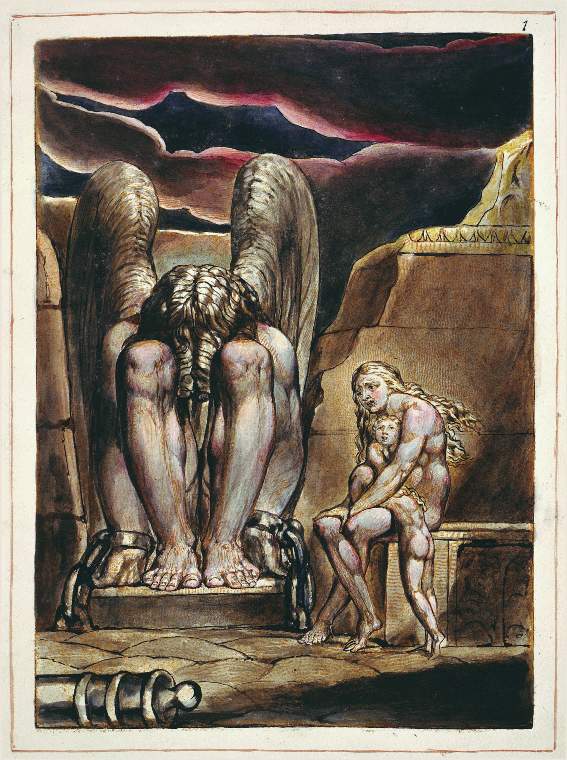

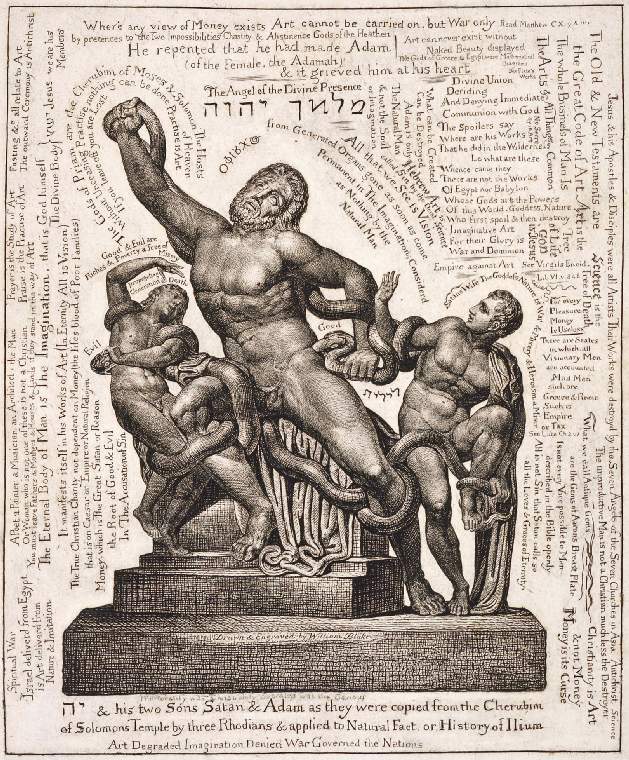

It's never a good thing if the main memory of an exhibition is the colour of the walls. Sadly, the Fitzwilliam's William Blake's Universe will forever be linked in my mind with the daffodil yellow of the final room. Strong colours are the fashion of the moment (a moment which is hopefully reaching its end) but they are always intrusive, an assertion of curatorial presence, even when you agree with the choice, and that intrusiveness is magnified in an exhibition of mainly small-scale prints and drawings where there is so much more wall on show.

Wednesday, April 24, 2024

'William Blake's Universe' (Fitzwilliam Museum until May 19 2024): Trying Too Hard to be Universal

It's never a good thing if the main memory of an exhibition is the colour of the walls. Sadly, the Fitzwilliam's William Blake's Universe will forever be linked in my mind with the daffodil yellow of the final room. Strong colours are the fashion of the moment (a moment which is hopefully reaching its end) but they are always intrusive, an assertion of curatorial presence, even when you agree with the choice, and that intrusiveness is magnified in an exhibition of mainly small-scale prints and drawings where there is so much more wall on show.

Monday, April 15, 2024

Angelica Kauffman (Royal Academy until June 30 2024): More Than Just a Woman Artist

Tuesday, April 9, 2024

'Frank Auerbach: The Charcoal Heads' (The Courtauld until May 27 2024): Creative Destruction

Auerbach is no ordinary portraitist. His subjects are familiar, familial, himself, seen here in repeat. He observed them over months, each sitting recorded and erased in a process of layering and repeat. The time and process are writ large in scuffs and tears and mends: whilst Auerbach's oils seem often a process of building up, here he is constantly breaking down. It is one of the many contradictions. Works which have been produced so slowly are utterly immediate, a flash of dynamic lines. Faces in close-up scale largely avoid our gaze, with hollows for eyes which tilt down or turn aside. Line and structure are etched with a rubber. Never has creation seemed so destructive.

There is no context given to these figures - no background, no space, little detail - but once you know the context, rawness hangs acrid in the air. Auerbach's own tragedy, refugee child of parents murdered in Auschwitz, and the long, lingering shadow of the Second World War: physical and mental scars, visible wounds, patches of poverty and endless, endless grey. The occasional slash of colour seems like an attack rather than a respite. The faces take on a ghoulish emptiness, stripped back, almost genderless. Yet the final, greatest paradox of this show is that humanity triumphs in the end. Auerbach's self portraits are thoughtfully challenging in their strong, straight stare. His cousin, Gerda Boehm, another refugee, his substitute parent, retains her poise and gentility. Helen Gillespie is all angles and sharp edges, positively glinting with wit. These characters breath and move, with subtle shifts of pose, lighting and expression across the different charcoals. Not ghosts after all.

Wednesday, April 3, 2024

'Entangled Pasts: 1768–now Art, Colonialism and Change' (Royal Academy until 28 April 2024): Difficult to Disentangle

In their absence, however, is blandness and vagueness. Too often I was left wondering why? Why was John Singleton Copley there? Because he, like Benjamin West was American, although there was no attempt to analyse their unique position as colonial but white? Because of the Black figure ignored in a caption which focuses instead Watson's survival to become Mayor of London? Because Copley was a big eighteenth century name they could get hold of? Similarly, Bowling and Gallagher are part of a room dedicated to the sea which is split awkwardly between the Middle Passage and whaling with a couple of second-rate Turners for good measure. The 'Constructing Whiteness' display feels especially thrown together. Frank Dicksee's laughably awful Startled doesn't need a caption which ties itself in knots over 'aryanising', 'nordic' and 'classical'. The slippery language emphasises a nettle ungrasped: issues of Academy racism are taken up to the Second World War and then glossed over. Surely this was the moment to acknowledge the embarrassing truth that Sonia Boyce, the first Black female academician, was only elected in 2016.

'Entangled Pasts' raises obvious comparisons with the recent, albeit much smaller, 'Black Atlantic' exhibition at the Fitzwilliam Museum - even some of the same works are on show. The Fitzwilliam went for tightly written text and impeccable lighting to create nuance and structure and maximise their limited exhibits. The Royal Academy, in contrast, underuses Barbara Walker's Vanishing Point and the beautiful Man in a Red Suit is shown, along with fine portraits by Gainsborough, Reynolds and others in a gloomily empty octagon. Isaac Julien's film deserves a better space: crowded watchers jostle with those trying to get through to the sculptures beyond and the tintypes behind are impossible to see. Meanwhile, Lubaina Himid's Naming the Money installation sprawls over two rooms, its impact lessened as a result. Inevitably, with 100 works and 50 artists, there are weaker pieces and you could certainly make the case for some judicious pruning.

In some ways 'Entangled Pasts' is a show of (mainly) good art, poorly served. But maybe that doesn't matter. Its big, rambling, inconclusiveness is in itself a metaphor for the entangled past it's seeking to represent. There are no easy answers or straightforward narratives. There are questions and problems and dead-ends. The curators resolutely refuse to tell us what to think, but thank goodness for that. What the show does - and arguably what it could have done even more - is pit the past against the present and let the results speak for themselves. Let's have more of the same.

A Kiss is Never Just a Kiss (for Valentine's Day)

Giotto, ‘Meeting of Joachim and Anne at the Golden Gate’, c.1303-6, Scrovegni Chapel, Padua, Italy (Wikimedia Commons) Y ou might think ar...

-

Johannes Vermeer Girl with a Flute 1669-75, National Gallery of Art Washington The National Gallery of Art in Washington reported in 2022 ...

-

Donatello, Judith and Holofernes , c1455. Palazzo Vecchio Florence If you ignore the crowds around the replica of Michelangelo's David i...

-

Milking Time , undated, St Louis Art Museum Willem Maris (1844-1910) was a Dutch artist, one of three brothers who were all associated with ...

_-_Self_Portrait_of_the_Artist_Hesitating_between_the_Arts_of_Music_and_Painting_-_960079_-_National_Trust.jpg/800px-Angelica_Kauffmann_(1741-1807)_-_Self_Portrait_of_the_Artist_Hesitating_between_the_Arts_of_Music_and_Painting_-_960079_-_National_Trust.jpg)