This is an exhibition of small scale works, including drawings, prints and pastels, and they ripple along the walls, punctuated by the odd larger piece, especially by Cornish, and splashes of wall colour, with protruding flats to create more intimate niches. One such contains a line of images of Cornish's wife carrying out everyday tasks: the wall text references Rembrandt but I was also reminded of Jean Francois Millet's solid yet tender portrayals of the Barbizon peasant community. Cornish conveys the same salt of the earth eternalism. His works are balanced by two Lowry bedroom interiors, the first an age of austerity, middle class and monochrome riff on Van Gogh; the second showing a visit by the doctor. There is a hint of Munch bleakness in the apparently banal everyday scene - recovery does not seem likely.

The curators make significant use of paired images, starting with two self portraits at the start. It is an obvious choice in a dual show but here has unexpected results: Lowry's 1927 The Procession pales alongside Cornish's 1947 view of Durham Gala. It is not just that the later is larger and more colourful, it successfully conveys both the sea-like mass of humanity above which the cathedral towers black in the background and the characterful, just the right side of caricature, foreground close-ups that Cornish is so good at. Lowry's crowd are all isolated in their own space, disconnected and alienated even on a holiday. His best work here foregoes the panoramic in favour of the quirky and the intimate: Meeting Point is divided centrally by a absurdly tall thin building into which assorted figures flow, women one side, men the other. My Two Uncle makes similar use of absurdist symmetry. It's a fine line between the surreal and the just plain cruel,

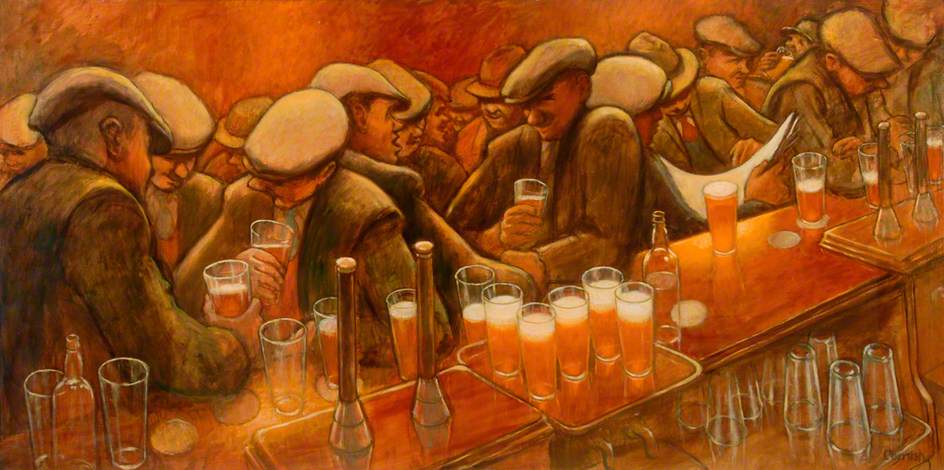

Cornish's best work has deceptive emotional strength. Busy Bar, one of the largest pieces here, seems painted with beer itself, the fuggy amber warmth of the background juxtaposed with the drown-your-sorrows pints lined up on the bar. The faces are animated, weary, sour; the atmosphere ambiguous. You don't need the pen and ink sketches alongside to believe the authenticity. And you cannot help but see these same figures trudge through the grey cold of Pit Road or agonisingly bent double in Going In-Bye. Facing it Pit Gantry Steps adopts a looser style, Cornish's usual chunky figures replaced by hunched blurs of Lowry-thin miners, lost in the mesh of metal, the noise and steam, dashes of orange as their lamps swing in their hands. The accompanying text quotes the artist remembering what he 'saw and felt as a boy' starting his first shift. All the labelling, along with a wall of videos, treats these works as personal and social history as much as pieces of art and ultimately this is a glimpse into a lost world of heavy industry and smoke blackened towns.

Kith and Kinship is in many ways an odd title. There is so little of either in Lowry's work and it suggests a nostalgic cosiness which is not at all what Cornish is about. Arguably, too, the artists rarely compliment each other, despite the curators' best efforts. Lowry, for all the fame of his matchstick crowds, excels as an artist of emptiness and oddness. Cornish emerges as an artist of strength and empathy, who deserves to be better known. I wish the exhibition was travelling to a venue down south, if only to prove that where there's muck, there's class.

No comments:

Post a Comment