Joseph Noel Paton is one of those artists who slips through the cracks of history. Famous and popular in his day, patronised by royalty and a friend and correspondent of leading artists and writers, his work now rarely merits more than a footnote. Despite obvious affinities with Pre-Raphaelitism through his crisp, clear colours, use of symbolism, and religious, literary and historical subjects, Paton never seems to have benefited the sexy romanticism that surrounds the Brotherhood. Perhaps the fact he was a happily married, father of eleven, Scotsman has something to do with it. It is debatable whether a small exhibition in Dunfermline is really going to shift the dial - it is a great pity for instance that the show isn't touring elsewhere, preferably south of the border. But this is a strongly curated, in-depth look at Paton's life and work.

I will confess that the first impression is not great. This is a display dominated by large and frankly fussily-designed wall texts, initially on white walls, and illuminating though they are, they are not aesthetically inviting. But the show turns out to be both larger, and more inventively displayed than those first impressions: green and red wall-colour blocks and a good mix of drawing and painting. Particularly impressive are the large scale cartoons for the Dunfermline Abbey windows which dominate one wall. The exhibition had been initially scheduled for the bi-centenary of Paton's birth in 2021 before Covid intervened, and in its original state was, I understand, to have included the artist's two great fairy paintings from the National Galleries of Scotland. These are a miss, despite substitute sketches, but it seems churlish to blame the curators for something so entirely outside their control. Paton's fairy subjects are represented here by The Fairy Raid, an unsettling cacophony of knights, fairies and magic in which meticulous observed reality collides with folklore and imagination. I'm not sure Paton was at his best with this multi-figure extravaganzas and it is perhaps his association with 'fairy' painting which is partly responsible for the dip in his reputation.

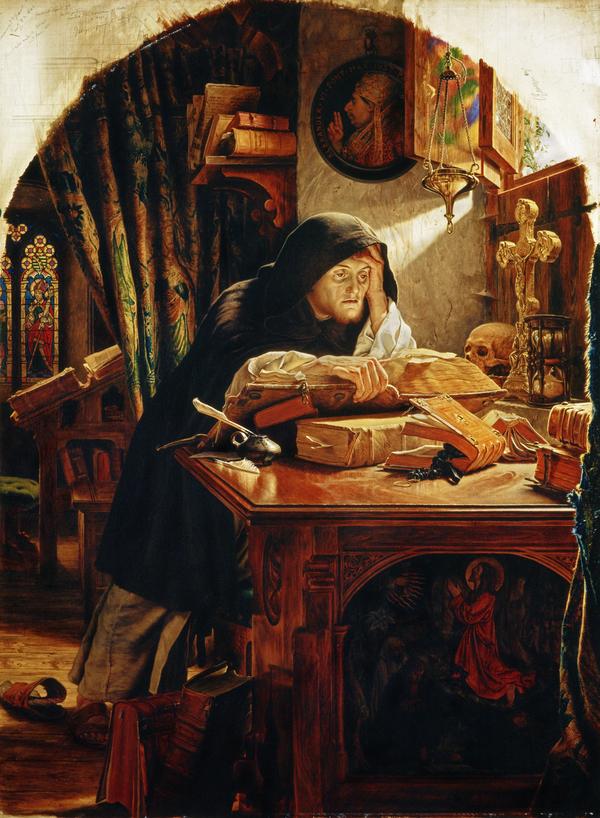

What is on show here gives both a themed view of Paton's career and a nice insight into his personal life, with sections like History and Heritage and Royal Connections. The sketches of his children, particularly of his youngest son who died at only five, are especially poignant. He repeatedly used his family as models, and his wife features, both unexpectedly - posing as Martin Luther - and emotionally, captured with Madonna-like intensity singing a lullaby to her child on her lap. These two paintings bring Paton's Pre-Raphaelitism to the fore, with tightly controlled compositions and copious, symbolic detail. But there is an emotional connection too - something which often feels lacking in the Brotherhood. Luther's spiritual doubt is written on his features with empathetic clarity in a way which William Holman Hunt fails to achieve in the work Paton's is often compared to, The Awakening Conscience.

Paton's enthusiasm for religious subjects links him back to both fellow Scot William Dyce, and the early nineteenth century Nazarenes. Another way in which he is often dismissed as conservative and establishment, although his choices within those subjects (Ezekiel's Vision of the Dry Bones), and his representational decisions, are often radical: the lowering Michelangelesque figure of Satan with flaming halo-like crown watching over a sleeping Christ, for instance. He was also, of course, not afraid to tackle tricky contemporary issues like the Crimean War and the so-called Indian Mutiny. His work also sits comfortably alongside the Academic style of Frederic Leighton and others, more Raphaelite than Pre-Raphaelite, exemplified by the strong colour blocks and effortless compositional group of Queen Margaret and King Malcolm Canmore. The difference, the uniqueness, which Paton brings is his Scottishness, both a sensitivity to the nation's history and folk culture, and a defiantly Romantic streak. With is boggy colours, chiseled faces and close-up intensity, At Bay is pure Walter Scott (or Outlander if you prefer your cultural references more up to date).

You could criticise An Artist's Life for not doing full justice to Paton. You certainly leave feeling he deserves a bigger show in a more prestigious venue. But that is a testament to the marvellous job that the Dunfermline curators have done: working with the material they've got they conjure up the breadth, the skill and the mind behind this fascinating artist. Thank goodness, we still have local venues with the will, the expertise and the support to mount exhibitions of this quality.

.jpg/1280px-Akseli_Gallen-Kallela_Autumn_-_five_crosses_(A_preliminary_work_for_the_fresco_in_the_Jus%C3%A9lius_Mausoleum).jpg)