Two significant exhibitions open in February 2023 which should finally lay to rest the myth that post-War Abstraction was an art form dominated by white, male Americans. The Whitechapel Gallery is showing 'Action Gesture Paint: Women Artists and Global Abstraction 1940-70' (Feb 9- May 7 2023) and in Newcastle, the Hatton Gallery has a retrospective of Wilhelmina Barns-Graham's work 'Paths to Abstraction' (Feb 11 - May 20). These are by no means the first exhibitions to showcase the work of women abstract artists. Dulwich's 2021 'Radical Beauty' looked at Helen Frankenthaler's woodcuts and in 2019 the Barbican quashed the belief that Lee Krasner was merely the wife of Jackson Pollock. However, coming on top of the head of steam generated by both the promotion of women's and global surrealism at the Venice Biennale and the break-out popularity of Katy Hessel's The Story of Art Without Men, this feels like a 'moment'. Perhaps women abstract artists can finally be seen and appreciated on their own terms and for their own work.

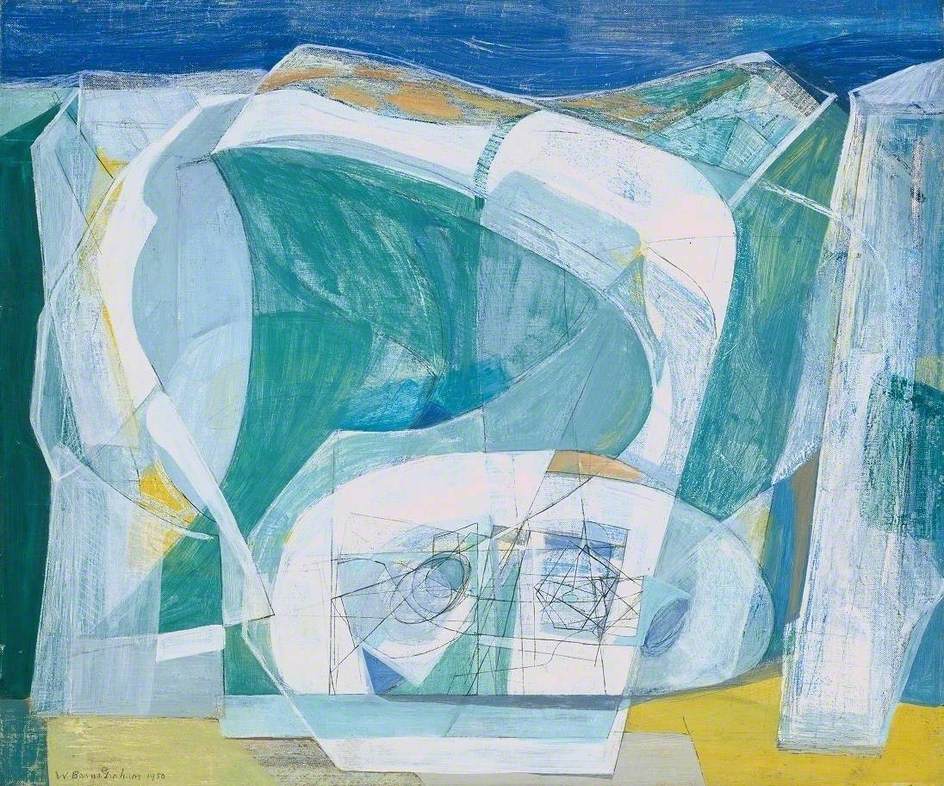

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham (1912-2004) is hardly a household name despite a prolific sixty-five year career. Born in St Andrews, she struggled against her family's opposition and to her studying art and ended up spending an extended period at Edinburgh College of Art 1931-9, partly through ill health. She received numerous prizes, including a scholarship to travel in Europe in 1939, but the war intervened. Instead, in 1940 she and fellow Scot, Margaret Mellis, moved to Cornwall, becoming part of the St Ives School which included Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson. Barns-Graham was a talented draughtswoman and watercolourist, but during the 1940s in St Ives, she started to experiment with Cubsit-influenced abstraction, flattening and simplifying the landscape forms which remained an inspiration throughout her life. In 1948 she visited Switzerland, and produced the first in what was to be a series of over twenty paintings of glaciers.

She maintained a studio in St Ives until her death, but after the War she was increasingly out of step with the competitive environment there. She moved briefly to Leeds with her husband, the poet David Lewis whom she had married in 1949, but they separated after only six years. After inheriting a house in St Andrews in 1960, Scotland once again became her home. British abstraction was dominated by the St Ives artists and Barns-Graham's reputation undoubtedly suffered because she was an ambivalent presence there. Only three of her works, for instance, were shown in the major 1985 Tate exhibition on the School. But her independent stance allowed her work to develop more freely: one of the characteristics of her career is that she continually moved forward, producing some of her most exciting and colourful canvases in the 1990s and beyond.

British abstract art sometimes seems weighed down by post-War austerity, the poor relation of America in scale and colour. Barns-Graham, who began her St Ives career, painting pallidly-lit, sometimes almost monochrome landscapes and townscapes, initially favoured a similarly Cubist influenced abstraction. However, her work through the 1950s showed a desire to explore a range of styles, from her introduction of rich colour, to strong linearity and the use of crisply geometric small cubes and circles. That experimentation intensified with her move back to St Andrews, with canvases exploring bold colour blocks and formalist titles.

No comments:

Post a Comment