Isobel Gloag,

The Knight and the Mermaid, c.1890, watercolour

The work of late Pre-Raphaelite and Aesthetic Movement British artists is often dismissed as hopelessly Romantic and old fashioned, a determined head-in-the-sand nostalgia which ignored the birth of the twentieth century in favour of a world of beautiful damsels, chivalrous knights, myth and magic. Yet these artists were popular, clearly feeding a broader need for escapism, and their work never existed in a vacuum hermetically sealed from Modernist movements, even when they were consciously rejecting them. This is especially true of Isobel Gloag (1865-1917), a Scottish artist who moved first to London to train at the Slade and then to Paris. She exhibited widely, including nineteen works at the Royal Academy, was a member of major oil and watercolour societies, and worked in a range of other media from stained glass to graphic art, despite a life apparently blighted by periods of illness, and a relatively early death aged 51.

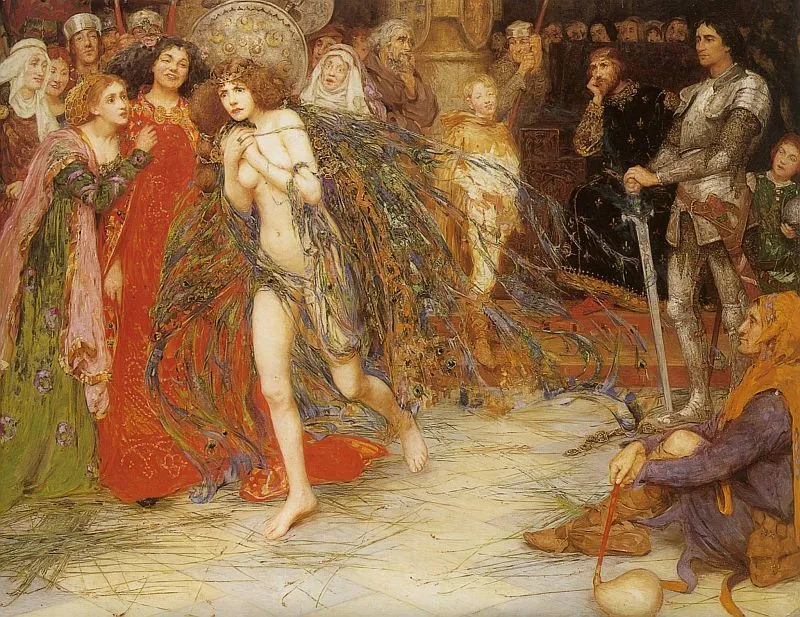

The Magic Mantle, 1898

There has been a concerted effort in recent years to 'rediscover' the work of female artists of this period and debunk the myth that aestheticism was simply the art of men painting beautiful women. Gloag however remains relatively unknown: there are very few of her works on public display, and many are known only through black and white illustrations. She is an elusive figure. She was not part, as so many artists of this period were, of an extended network of producers either by family or marriage; and little has been written about her. Yet she is so much more than a run of the mill Pre-Raphaelite copyist: her work has a freedom and expressiveness which is akin to Sargent's and her rich, decorative colouration is reminiscent of the Austrian Secessionists, or of Vrubel or early Kandinsky. Her subject matter was hugely varied, from bang-up-to-the-minute images of high fashion to historic representations of a world of crinolines and Victorian restriction; from religion to female nudes; narrative to pure aestheticism. Gloag's work is always - to use adjectives ascribed to her in a 1906 review - beautiful, vital, lively, and always fascinatingly difficult to pigeonhole.

A Legend of Provence c. 1894

The more obviously pre-Raphaelite works include Four Corners of my Bed (c.1901) in which four angel musicians watch over a baby. The confined space, with depth represented by the small-scale mother by the window, the profile kneeling foreground figures, the use of music and the quasi-religious sentiment link this back to images by Rossetti or Burne Jones.

Four Corners of my Bed, c.1901

However, Gloag's unique style is better characterised by The Knight and the Mermaid, sometimes seen as representing Keats' 'Lamia' but in reality a more akin to Medieval tales like that of Melusine. The artist exploits the subject as a representation of seduction and eroticised feminine power, themes which she explored in Rapunzel. In both works, a similarly clad knight is physically ensnared by the female body - the tail and hair - and by the precipitous vertical composition and claustrophobic sense of space. The dreamily pale palette of The Knight and the Mermaid, exaggerated by the apposite choice of watercolour, is more like that of French artists like Jules Bastien Lepage than of Pre-Raphaelite richness.

Rapunzel, c.1901 (illustration from The Magazine of Art)

An even stranger work is The Magic Mantle (1898) based on an Arthurian story of a cloak which could only be worn by a pure woman. The painting shows one of the ladies of the Camelot court whose infidelity has quite literally been exposed fleeing as the mantle disintegrates into drifts which resemble peacock feathers. It is an uncomfortable image where the women, some mocking, some shocked, take centre stage and the male figures, relegated to the background observe with almost indifference.

A Bacchante and Fauns, c.1912, Museum of New Zealand

It also seems uncharacteristically judgmental for an artist who elsewhere seemed to relish unabashed female nudity. A Bacchante and Fauns (c.1912) shows a laughing figure, unconcerned by her nakedness and utterly disinterested in any supposed, male viewer. The furs and fabrics, together with the loose handling of the background create a sensual world of softness and pleasure, whilst the enclosed space and cut-off composition reinforces intimacy.

The Woman with the Puppets c 1915, Hugh Lane Gallery, Dublin

The Woman with the Puppets (c.1915) shows a similarly self-absorbed nude, but here Gloag dispenses with any traditional mythological setting, and adopts a pose which in no way indulges the viewer. The woman is amusing herself by playing with puppets of men, perhaps slightly heavy-handed in its symbolism but nevertheless striking; and a detail which links the work back to Gloag's earlier fairy-tale paintings.

The big, bold brushstrokes, seen especially in the draperies, are characteristic of Gloag's later work and demonstrate how far she moved away from her earlier Pre-Raphaelitism. Similarly, her contemporary portraits of women, now only known through black and white images, have a dash and verve which characterises the sitters as strong, independent figures. One can only suppose that Gloag saw herself in the same light.

No comments:

Post a Comment