William Morris would have loved the Ashmolean's 'Colour Revolution'. It is crammed full of beautiful, often useful things and it provides an equally beautiful, useful survey of Victorian culture, taste and innovation, their priorities and their prejudices. It is larger than I expected, more interesting, full of detail and well presented, albeit sometimes frustratingly dingy, for obvious conservation reasons. Ultimately, however, it is unsatisfying: stories left unfinished, avenues unpursued, threads dangling.

The main problem is that the exhibition starts with a flawed premise: we have a mourning dress, a black and white photograph, a Dickens quote, all setting up the narrative that the past is a dreary place. Yet anyone who knows anything about nineteenth century art and design, knows that it's all about colour, pattern and excess. The interesting story here is not the manufactured narrative of a 'colour revolution', but rather the real revolutions in manufacture, technology and trade which allowed the Victorians' love of colour to permeate through society and across the world. The exhibition does a good job of looking at potentially dry topics like the discovery of aniline dyes, advances in electroplating; and the costs involved, to individuals hanging arsenic-green wallpaper, or lead-painting majolica, to the wider world (natural dye producers in India), and to nature - thousands of hummingbirds sacrificed to fashion each year. This is where the exhibition is strongest and most innovative.

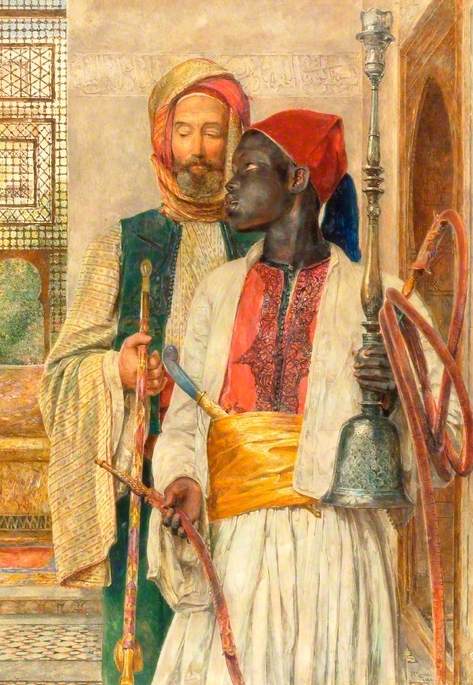

Interesting too is the focus on the 1862 great(ish) International Exhibition which rarely gets any mention. William Burges' Great Bookcase is an arts and crafts masterpiece. A Daughter of Eve, her skin colour achieved with electrotype bronze, stops you in your tracks. The curators do well, in this age of didactic labelling, to let the image speak for itself: abolitionist pride in the midst of the American Civil War off-set by the statue's relegation to a trade stand. Not art but commerce. The fashion - not usually my thing - is also well-chosen and well-presented. Gaudily-striped stockings (for men and women) and a purple aniline dress which seems to have walked out of a Pre-Raphaelite painting; iridescently-gleaming necklaces which on closer inspection are made from hummingbird heads and beetles. Finally, the show dips into the Victorians' inspirations: from history, from the Middle and Far East, and from nature itself. Again, there is luscious Kashmir paisley, jewel-like Medieval manuscripts, ubiquitous Japanese prints, but the displays only scratch the surface.

JMW Turner, Venice, from the Porch of Madonna della Salute, c.1835,

The paintings are colourful. but hardly revolutionary. Many of the works are overfamiliar loans from the Tate - beautifully lit here and still a pleasure to see, as old friends always are, but Mariana and April Love are too-obvious curatorial choices. The Turner view of Venice on loan from the Met is on another level. Not one of his too-vague sunlight and air canvases but a luminous explosion of colour, rich reds and blues bleeding out from the boat in the centre of the painting like dye in water. Albert Moore is also nicely showcased, with a run of three near-identical paintings, differing only in their colour choices; and placed alongside Whistler his dreamily-soft palette takes on a new, more radical edge. Both artists are a welcome boost to the last room which seems a little low-key. Perhaps the 'Yellow Nineties' simply cannot compete with the intense colour and pattern already shown, perhaps it is just too difficult to buy into the immorality. Although Grasset's 1897 poster showing a morphine addict injecting her thigh is genuinely shocking.

There is a lot that the Ashmolean doesn't focus on. William Morris is poorly covered. Art Nouveau surely deserves a mention. The importance of colour to the Spiritualist movement is ignored, despite a focus on High Anglican design. But it is always churlish to dwell on what isn't in an exhibition. Ultimately this is show of intensely beautiful detail which also manages to convey big ideas, like Darwin's theory of sexual selection, with almost throwaway ease. You leave with a vivid sense of 'Victorian art, fashion and design', and a desire to find out more.

I want to go back. You can't really have a better recommendation.