Sunday, April 30, 2023

'Action Gesture Paint' (Whitechapel Gallery until May 7 2023): A Festival of a Show

Monday, April 24, 2023

'The Rossettis' (Tate Britain until 24 September 2023): It's the Dante Gabriel Show

The Pre Raphaelites, Rossetti in particular, produced marmite art, and for me it's best spread thinly. But Tate Britain's The Rossettis show promised something more - a pluralised approach and a emphasis on radicalism, so I went with an open mind. It started positively. The sound showers of Christina Rossetti's poetry were novel, but for an exhibition which purported to place such an emphasis on combining words and pictures and describes itself as 'immersive', that first room was oddly sparse. There was a sense of 'lets get the poetry out of the way' - the showers pretty much dried up and the poetry was largely left to Gabriel from then on.

This is the main problem with a show which claims to be about the Rossetti family by birth and marriage, but ends by giving two members - Maria and William - very short shrift, and by the last two rooms is all about one man. I'm not blaming the curators: they were set an impossible task. Poetry is never going to hold its own with paintings in an art gallery - although they could have made a better job of combining the two. Equally, whatever your views on Elizabeth Siddal's art, the reality is that she died young, and produced a relatively small body of small scale work. In gallery terms she simply can't compete with the prolific large scale production of her husband. The curators attempt to circumvent this imbalance by a tightly choreographed like for like approach with both artists presented as working off each other. This works well on the gallery walls: the juxtaposition of Siddal's Lady Fixing a Pennant to a Knight's Spear and Rossetti's The Tune of the Seven Towers, for instance, neatly illustrates compositional and subject similarities whilst highlighting Rossetti's greater interest in surface pattern and complexity.

Unfortunately, the approach creates a very insular view, at odds with the current narrative that Siddal deliberately approached the PRB with the aim of becoming an artist, and that she moved away to study at Sheffield School of Art and was financially supported by John Ruskin. The exhibition is also oddly coy about their personal relationship, indeed Gabriel's relationships with women generally. A particularly extreme example is the caption which suggests they delayed marriage to avoid children, implying a platonic courtship which seems hard to believe. Whilst the show is clearly going out of its way to avoid both a biographical Desperate Romantics narrative and one in which Siddal is reduced to mere muse (hence no Ophelia), the lack of context is disengaging and does her no favours.

The second thrust of the exhibition is radicalism, and this too the curators struggle to sustain. On a political level, and despite his Italian revolutionary family background, Gabriel is never more than a youthful dabbler. Found is a failed attempted to jump on the 'fallen woman' bandwagon - you can go upstairs to see Holman Hunt and Spencer Stanhope make a better fist of it. If you have to stretch to drawing out contemporary parallels from a drawing of feudalism - as the curators attempt with Millais' A Baron Numbering his Vassals - then you are surely losing the argument. The case for artistic radicalism is just as shaky. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood were controversial, but because they were going backwards not forwards. And Rossetti was by no means the most controversial of the bunch: just compare his Girlhood of the Virgin with Millais' supposedly blasphemous Christ in the House of his Parents (another work you need to go upstairs to see).

Equally, Rossetti's contribution to aestheticism, which dominates the second half of the exhibition, may be significant, but is conservative compared with that of, say, Whistler. His idea of art for art's sake is essentially to paint the same ideal of feminine beauty over and over again, as the last two rooms of the show demonstrate. Even the exhibition's attempt at illustrating aesthetic design falls flat: a couple of pieces of furniture and some, admittedly very lovely, reconstructed wallpaper. You get more appreciation of contemporary taste from a small photograph of Frederick Leyland's drawing room displayed later in the exhibition.

If you strip it back, this is really a retrospective of one Rossetti: all Gabriel's main works are there and the last two rooms are a beautiful triumph, worth the admission price in their own right. The reuniting of the Leyland triptych of Mnemosyne, The Blessed Damozel and Proserpine is like three movements of a symphony, lush and absorbing, and the perfect - missed - moment for a sound shower. For me his best works are his small, intense watercolours where constricted space is further reduced by rich surface pattern. Here, surely, Rossetti is at his most radical: for all their narrative drive and Medievalism, there is an abstraction and an exploration of the medium which is utterly lacking in his largescale oils. The show also takes the trouble to show his process through the various attempts to resolve Found, and through the use of models in The Beloved.

Perhaps The Rossettis (plural) was never going to work: the Tate's own website only bothers to include Gabriel's paintings on their promotion page. Even if you take away the plural, it's very difficult to read highly finished, dreamy sensuality as a radical statement. Ultimately, however, this is an exhibition which fails to grasp the nettle. Rossetti's art cannot be understood without referencing his attitude to, and his relationships with, women, including Siddal. By the end of the show, I realised that the unhealthiness of his abusive dependency on a succession of models is what I find so unpalatable in his art. There's nothing beautiful about it.

Sunday, April 16, 2023

After Impressionism: Inventing Modern Art (National Gallery until August 13 2023): Over-Familiar Faces

There's been a lot of negative publicity about this exhibition, centred around the lack of female artists on show; and that, coupled with the sense of weariness at the prospect of more the same old Post-Impressionist names left me pretty unexcited. In fact, it starts very well. The first few rooms are a tightly curated run-through of French art trends from the 1880s to the turn of the century. The big names are there, justified both by the quality of the works chosen and the thoughtful labelling.

Even if you've already overdosed on Cezanne and don't feel the need to look at The Bathers again (it is after all permanently on show at the National Gallery), there is plenty of interest. His portraits were thin on the ground at the Tate show but here you get the glorious Ambroise Vollard (1899), suit and background alive with brush-marks and disparate, vibrant colours, eyes dead and yet strangely characterful. It's a great pity that Picasso's Vollard portrait was not available. Degas is surely an anomaly in this company - if his art moves Impressionism on, then the same could be said of others in the group - but Gauguin and Van Gogh shine. Personally, I'm past the biographical angst generated by Nevermore. As an object in itself, it is wholly successful in conveying fear, mortality, mystery and spiritual dread. And whenever you see Gauguin's work in the flesh his use of colour is just astounding: the still life here lights up the room.

There's an equally good summary of pointillism, symbolism and the Nabis, although the paintings are less compelling. Claudel gets a look in, with a disappointingly conventional image which does little in itself to justify her inclusion. Similarly, Toulouse-Lautrec seems undervalued - his Tristan Bernard at the Velodrome Buffalo (1895) is wishy-washy. And, given the inclusion of Picasso's lurid and leering Gustave Coquiot (1901), an example of his Moulin Rouge works would have been a useful comparison.

However, the exhibition then becomes a vague 'this is what was happening in...' survey which makes relatively little effort to either link the paintings back to France, or to explain how these artists were 'inventing modern art'. We inexplicably have two large paintings by Corinth but no Italian Futurism, no Russian art (which is perhaps understandable), no homegrown talent, and precious little German Expressionism.

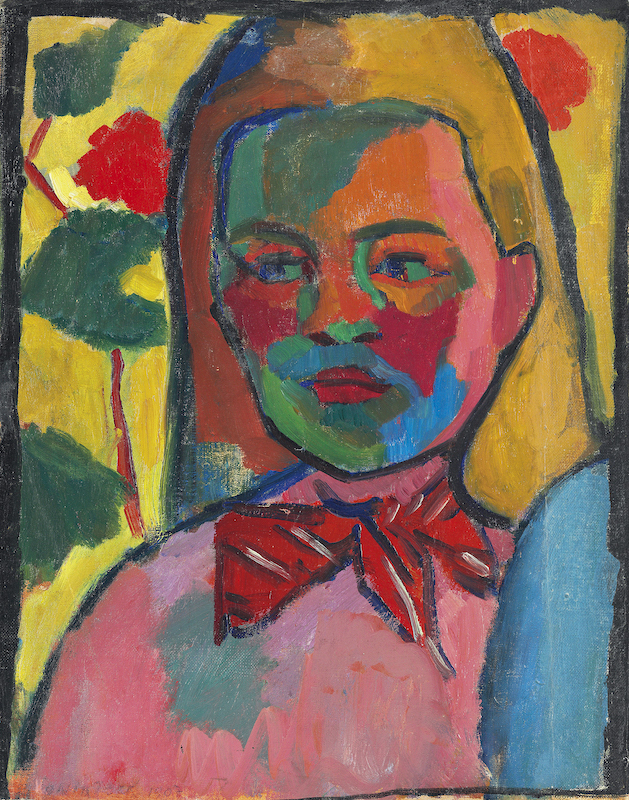

I would have no difficulty walking through rooms of early twentieth century art, but given the range of loans and the effort which had clearly been put into this show, I expected a more exciting selection. A Munch field of cabbages, especially when placed next to The Death Bed's existential bleakness, seems only there to fill up a space. Two full length, full frontal Klimt portraits seems one too many. A small jewel-coloured Kandinsky landscape leaves you desperate for more. Yet Delaunay's Young Finnish Woman is staggering: Fauvist colour with psychological punch. It's only in the last room that things come together again. Picasso's Portrait of Wilhelm Uhde is a fabulously characterful study even without the Cubist experimentation. Together with the solid chunkiness of Woman with Pears, it's a reminder that although Picasso might now be deemed 'problematic', he also seismically shifted the world as we see it. An ever-decreasing naturalism sequence of Mondrians brings things to a satisfying conclusion. You can leave feeling that you have seen 'the invention of modern art'.

There is an abundance of wonderful artworks in the National Gallery's exhibition, but both the ambition and the achievement are disappointing. Haven't we moved on from a linear 'birth of modernism' narrative? Isn't it time to acknowledge the limitations of a monolithic 'Impressionist era' approach? If you are going to use either of those arguments today, you need to make a much better case than After Impressionism does.

Saturday, April 15, 2023

'Breaking the Mould' (Walsall New Art Gallery until April 16 2023)

Very belatedly I head to Walsall to see Breaking the Mould: Sculpture by Women Since 1945, an Arts Council exhibition which has been trundling around various galleries for the best part of two years. The New Art Gallery at Walsall, built with millennial optimism, looks and feels precarious. The asymmetric stack clad with terracotta tiles and slashed with horizontal windows seems like a giant Jenga ready to topple. The 'waterfront' square surrounding it is flanked by disused dilapidation and the canal basin features a stagnant dam of plastic bottles. Inside the place is quiet: the art library locked, the roof terrace out of bounds. Its beautifully warm and welcoming wood and very human proportions are crying out for visitors. The experience is blighted by a fear for its future.

The gallery is blessed with a tremendous permanent collection, far removed from the usual provincial museum diet of second rate 'old masters' and Victorian taste purchases. The Garman Ryan Collection is an eclectic but careful acquired selection of everything from ancient Roman fragments to Durer woodcuts and a Modigliani; it's displayed thematically in a labyrinth of small rooms you don't mind getting lost in. And at the moment it's enriched by the sub-curation, Here and Queer, subtly distinguished by rainbow labels and accompanied by a well-produced free guide which again makes me worry about expense. There is literally something for everyone here, from moments of unexpected excitement - John Wishart's Moths on a Blue Path - to familiar jolts of pleasure. Epstein's Kitty with Curls alive with earnest youth and intensity contrasts with Freud's Kitty, small and precise like an Early Renaissance profile portrait. A mean and moody Constable study; a Gericault nude, all twisting tension. A Medieval Spanish wooden Christ, arms sorrowfully outstretched; a fragmentary Roman hand. And some of them are sponsored by locals and visitors - my anxiety levels dip slightly with each lovingly personalised label.

These domestic galleries give way to more conventional high-ceiling, white cubes on the third and fourth floors and it's here that Breaking the Mould is on display. Why just women sculptors? All the usual worries about positive discrimination surface. Are visitors expected to see signs of 'woman-ness' in this work? What you actually get is a varied selection of sculpture which includes most of the big names - Hepworth, Barlow, Chadwick, Lucas, Parker - split into three not particularly enlightening themes. Formed, Found, Figured, Are we sticking to 'F' for Female'? On first sight, it is curiously bland. There is nothing very large or very controversial. Phyllida Barlow's huge rough and ready Dunce dominates one room, like an unruly gatecrasher at a cocktail party.

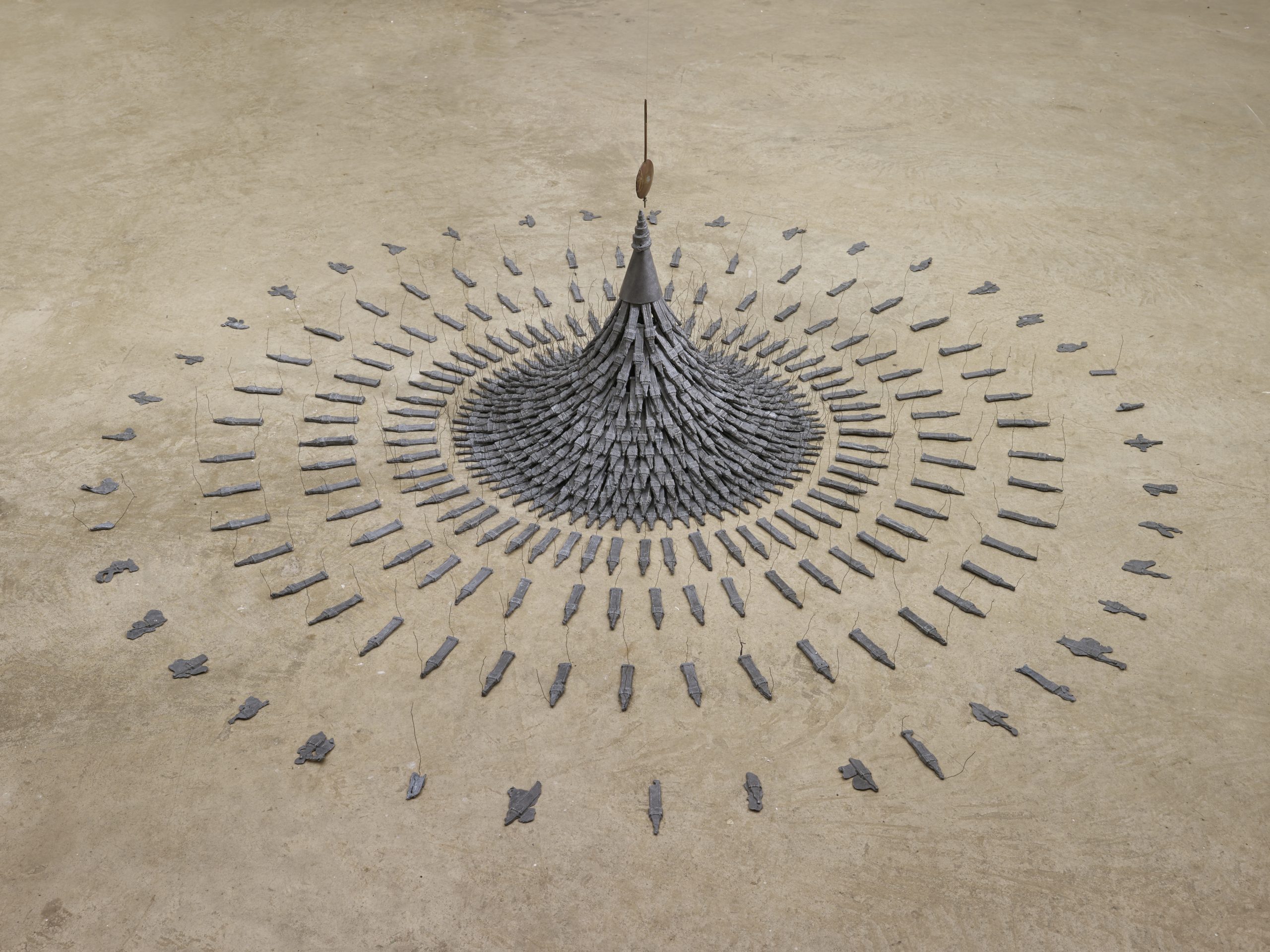

The most effective pieces are the most intriguing: Mona Hatoum's + and - is mesmerisng: mechanically transporting you back to the childhood pleasure of making patterns in the sand with Zen-like repetition and beauty. Sarah Collis and Wendy Taylor can't help but bring a smile with their deceptively simple 'look twice' cleverness. Cornelia Parker's Fleeing Moment seems to defy gravity and time as ever-decreasing Big Bens fan out in a frozen 'splash'. Elsewhere it is the material which triumphs: Hepworth's sleek mahogany and Lucas' stuffed tights beg you to touch. I stare at Rachel Whiteread's Untitled (6 spaces) desperate for it to wobble and wanting to lie on the floor to look into its gelatinous mystery. Jann Haworth Calendula's Cloak, a riot of colour in a space dominated by neutrals, seems a forerunner of Hew Locke's Procession: sinister, celebratory and mythic.

Wednesday, April 5, 2023

'Donatello: Sculpting the Renaissance' (V and A until June 30 2023): Emotional Relief

There was always going to be disappointment: a Donatello exhibition without any of the big bangs. No Judith, no bronze David, no St Mark, no Zuccone, no Mary Magdalene. And the V and A does itself no favours by having the biggest bang they've got as the first thing you see. The marble David, Donatello's first major commission, often feels like the boring, fully clothed brother of that famous saucy nude, but here its clean beauty has space to breathe. The deep veining of the marble pulses like veins on the skin, the human details of puckered cloth creates intimacy, the over-long neck and small head make him impossibly young and yet undeniably noble. And the curators have an extra trick, a cut-through arch to the end of the show and an almost but not quite mirror-image of the David, time- and restoration-ravaged. You don't fully appreciate the cleverness until the end.

It is the staging of the exhibition which really elevates it. The open space of the Sainsbury Gallery retains an airiness, with long vistas across to the big pieces and shadowy alcoves for the drawings; the deep, calm aquamarine is a perfect foil to marble, bronze and gold; the lines are clean, the captioning just short of twee (there were a few too many 'charmings' for my taste). And the lighting is superb: the poignancy of the shadow cast by the tattered drapery on the bronze crucifixion catches in your throat. There is so much to admire that it seems churlish to dwell on the absences. There is a genuine, but not entirely successful, attempt to explain the processes: the curators seem overly concerned with Donatello's training as a goldsmith, and his skill as a draughtsman - tricky to illustrate when neither gold-work nor drawings survive. There is little sense of his career and stylistic development. Too little attention is paid to his skill as a stone carver, or his technical development of bronze casting, and his exploitation of wood is absent. Instead we get a lot of terracotta; a lot of 'after', 'studio of' and 'attributed to'. Sometimes it feels as if he is being reduced to a producer of putti and churned out Virgin and Childs.

I'm being picky. What you do get is some of the most beautiful, affecting and virtuosic sculpture that was ever made. The Pazzi Madonna, so softly carved out of crisp marble, literally brought tears to my eyes. The noses of mother and child almost desperately press against each other, separated by a shadow which seems like a wound; Christ's tiny clutching hand and almost laughing open mouth, contrast with the downcast sorrow of her premonition. The Miracle of the Mule (c.1446-50), usually half unnoticed in the Basilica of S. Antonio in Padua, is so complex, so clever, that you can look at it for hours. Donatello's ability to work in ultra-shallow riliveo schiacciato is easy to take for granted: mathematical perspective, straightforward to accomplish with drawn orthogonals on paper, is skewed by even the most shallow relief. Here Donatello juggles perspective, multiple figures, emotional range and a complex triple-arch composition which you can see caught Mantegna's eye. The whole surface is alive with texture, light and reflection. For me, though, the absolute highlight is the late Lamentation, a rough hewn slab of raw emotion. Mary's haggard grief is reminiscent of the wooden Penitent Magdalene. Snaking drapery, hair and limbs create an inverted bacchanale of despair that dissolves time - quattrocento could be the early twentieth century.

The exhibition ends with a slightly pointless section on 'Donatello's legacy' which allows the V and A to show their 19th century copy of the bronze David (1440), but surprisingly not their Judith and Holofernes (c.1455). It emphasises the show's weakness at presenting the big picture: those two copies summarise his range, and his real legacy can be seen, not in trite tributes, but in Rodin, in Kollwitz. You leave with a very good sense of Donatello's relationship with Michelozzo; of the studio system which operated in the early Renaissance; of the importance of Padua as an artistic centre. But you have very little sense of Donatello as a man (which could be deliberate); of his ability to create emotional and psychological insight; of his versatility, or indeed of his artistic influence. In this sense it's an exhibition for the enthusiast and the scholar, rather than the general public, which seems a great shame.

Saturday, April 1, 2023

Berthe Morisot: Freedom in Restriction

For a long term it felt like Berthe Morisot (1841-1895) was The Woman Artist. In the early 1970s, when New Art History was gaining ground her role as an Impressionist, but one who also represented the social restrictions of nineteenth century women was much written about. The ubiquitous popularity of Impressionism has receded, and the boom area for feminist art history now is arguably the Baroque, with Artemisia Gentileschi leading the way, closely followed by artists like Lavinia Fontana. Morisot seems marooned in a backwater, neither a big enough name, nor enough of a novelty to garner interest. Her resolutely female domestic subject matter nowadays seems tame, almost like a flag of surrender in comparison with those seventeenth century women who so obviously colonised male artists' territory. An upcoming exhibition at Dulwich Picture Gallery (starting 31 March 2023), whilst a welcome and long overdue examination of Morisot's work, is positioning her in the context of eighteenth-century French painting and thus seems at risk of reinforcing ideas of a feminine aesthetic in her work.

Morisot, as she is presented nowadays, had it pretty easy. She came from a wealthy enough background to indulge her enthusiasm for painting with private tutors and chaperoned visits to the Louvre. She chose a husband who allowed her to continue to paint, in comparison with her sister who gave up her art to become the wife and mother society expected. Morisot's husband, Edouard Manet's brother, Eugene, is often presented as a shadowy figure persuaded into a marriage of convenience which allowed the two artists to remain close. She had only one child and so never became overwhelmed with domestic duties in the way other would-be women artists of the time were. She could afford to produce uncommercial work, and at her death over 80% of her paintings remained in the family's possession. We like our artists to struggle and somehow all these advantages seem to be held against her and her images of seemingly contented domesticity and bourgeois virtue.

The irony is that Morisot, in terms of her drive and activity within the Impressionist circle, was nothing like the little bourgeois woman sitting at home which her paintings seem determined to portray. She withstood considerable family pressure to give up her painting, finally agreeing to marry at the age of thirty-two, long after she was considered an old maid. She made a conscious decision to exhibit in what would become known at the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874, despite having previous Salon success and against the advice of Manet: she was savvy enough to see the benefits of a show which enabled her to show nine varied canvases in a less crowded and competitive environment. She similarly auctioned her work at the 1875 Hotel Drouet sale, achieving the highest price of the day. At the second Impressionist exhibition she showed more works than anyone else, and she participated in all but one of the rest, missing only the one after the birth of her daughter. Her final letter expressed hope for a future museum dedicated to Impressionism. It is a damning testament to the continued sexism of the art world, that Morisot, so deeply embedded into the Paris Impressionist circle, is not only still treated as an also-ran, but that this second-class status goes largely unchallenged.

The Impressionist movement was frequently described as feminine by contemporary critics. The unfinished nature of the work, the emphasis on transience and changeability, the importance of colour were all seen as womanly. Morisot herself was criticised for not having the masculine stamina to finish her canvases. Today we might not recognise such gendered criticism, but the perceived prettiness of much Impressionist art and brushwork which might be described as feathery, light or even fluffy continues that feminine discourse. Yet in terms of technique, Morisot is resolutely a-feminine, anti-pretty: she frequently applied paint in rapid, dashed strokes creating a sense of hurriedness, certainly, but also suggesting vigour, dynamism, sometimes even annoyance. Her colour is less pastel prettiness than cool and clear, influenced by her time as a pupil of Corot but also following a range exploited by other French naturalists of the time. Like Manet, she retained a fondness for black using it sparingly but effectively for emphasis. Her work shows such a steady development away from 'finish' that in canvases like Woman and Child in a Meadow at Bougival the figures dissolve into a semi-abstract storm of brushmarks. Only in the last years of her life did her palette warm, her interest in line return and her brushwork soften, to create works with an affinity to Auguste Renoir. Her portrait of her daughter, Julie Daydreaming, is reminiscent of Edvard Munch in its sinuous line, plain background and colour blocks creating an enigmatic mood: symbolic white, loose hair and the hint of something red in the teenager's hand.

Morisot's subject matter, with its focus on the routine and restriction of bourgeois domesticity, is often taken as another marker of femininity. Yet, whereas her contemporary, Mary Cassatt, seems consciously determined to catalogue women's lives, becoming a female 'painter of modern life', Morisot seems almost oblivious to her subjects, their faces erased, the bodies lost in the haze of brushwork. Cassatt painted female subjects at the theatre, captured as if by accident in the public gaze; Morisot's At the Ball features a dressed up, posed woman apparently sitting at home. She painted what was to hand for her own convenience, thereby avoiding the difficulties and awkwardness she described when trying to paint plein air in public. And although her closeness to those subjects - her sister, her husband, her daughter - shows through, the emotion is almost accidental. There are psychological readings of entrapment and erasure; some have focused on her supposed empathy for servants; another argument suggests that she was deliberately choosing her battles - innocuous subjects to balance her radical technical choices. All this slightly missing the point. What she is really interested in is the act of painting itself, the transmission of transience onto canvas.

Berthe Morisot is a classic example of the institutional sexism which still haunts the art world. Her subjects are seen as evidence of the restrictions under which she lived her life, as a middle class woman in the late nineteenth century, and by implication her art is belittled by those restrictions. Her gender means that she is seen as a woman first and an artist second, so subject matter and biography always seem to take precedent over the technique, and her truly radical use of paint is never fully explored. Appreciated and applauded at the time, interest in her work very quickly dwindled after her death. Surely it's time to move beyond Morisot the 'woman Impressionist' (to quote the title of the 2018 Barnes Foundation exhibition) and see her as an integral and innovative member of the movement.

A Kiss is Never Just a Kiss (for Valentine's Day)

Giotto, ‘Meeting of Joachim and Anne at the Golden Gate’, c.1303-6, Scrovegni Chapel, Padua, Italy (Wikimedia Commons) Y ou might think ar...

-

Johannes Vermeer Girl with a Flute 1669-75, National Gallery of Art Washington The National Gallery of Art in Washington reported in 2022 ...

-

Donatello, Judith and Holofernes , c1455. Palazzo Vecchio Florence If you ignore the crowds around the replica of Michelangelo's David i...

-

Milking Time , undated, St Louis Art Museum Willem Maris (1844-1910) was a Dutch artist, one of three brothers who were all associated with ...